The Simons Center is please to present a piano performance by Leon Livshin. This event is free and open to the public.

Wednesday, April 23, 2025

5:00pm

Simons Center Della Pietra Family Auditorium, room 103

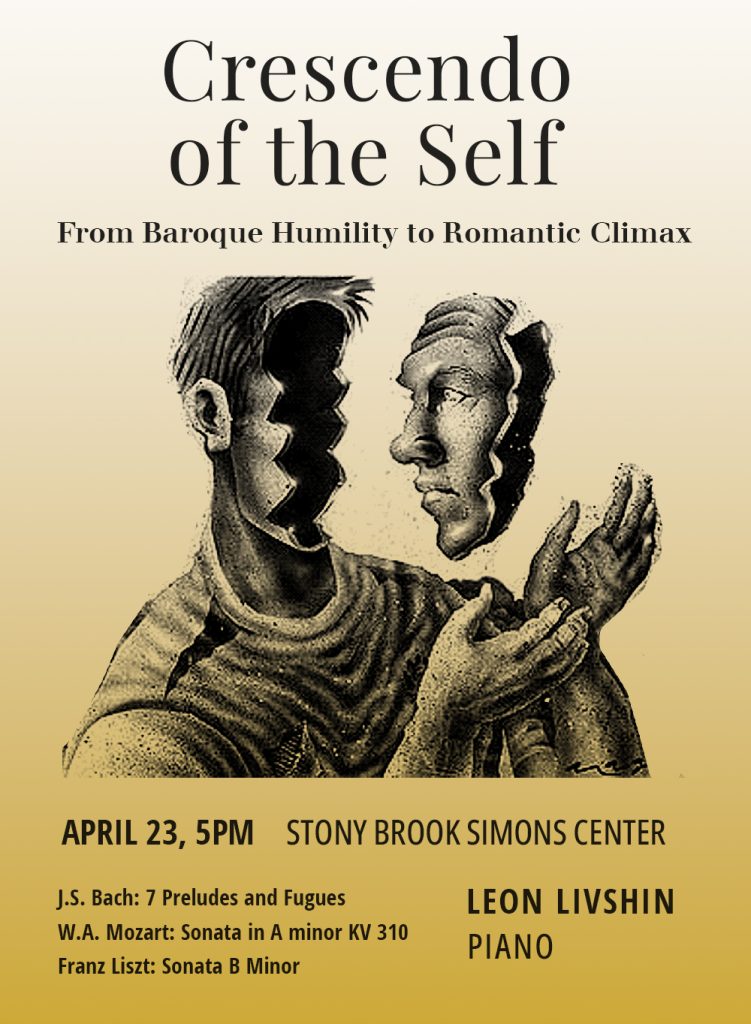

Crescendo of the Self: From Baroque Humility to Romantic Climax

Bach 7 Preludes and Fugues

Mozart Sonata in A minor KV 310

Liszt Sonata B Minor

Featuring: Leon Livshin, piano

About The Program EGO IN THREE STYLES Could we look at Baroque, Classicism, and Romanticism not as frozen chapters from art history textbooks, but rather as living, breathing phenomena—full of passion, constantly shifting? What if these aren’t merely “periods,” but ways of thinking, attempts to come to terms with the chaos of existence itself? Romanticism and Baroque—they’re like two neighbors who pretend not to get along, yet constantly run into each other. Let’s start with Baroque, a sort of elderly perfectionist who keeps lecturing everyone about how life should be lived: the world is vast, incomprehensible, and if you don’t organize it somehow, you’ll quickly lose your marbles. Baroque takes chaos, neatly packs it into harmonious forms, and ties it up like a beautifully wrapped gift. But the world resists packaging—it constantly bursts out, reminding us that we’re not masters of our fate, but rather puppets. (Maybe this explains all those exaggerated gestures in baroque operas?) No matter how hard we try, chaos eventually seeps through. Perhaps that’s why Baroque tends toward monumental forms: if chaos is huge, then order has to be equally grand. Hence the toccatas, suites, preludes and of course fugues—the peak of polyphony—where chaos seems tamed, yet the soul still trembles. Gradually, Baroque slides gently into playful yet rigid lines of Classicism, obsessed with even greater clarity, symmetry, and order. Classicism, if you like, is Baroque’s younger sibling who managed, at least temporarily, to tame chaos. Everything here is neatly structured, ranked, filed precisely on shelves. A step away from the ideal is practically considered an escape attempt—and anyone daring to step out of line (like Mozart with his Requiem or the sonata I’m planning to play) gets figuratively “shot down” without warning. Can there be something like romantic Classicism or baroque Romanticism? And here enters our third character—Romanticism—protesting loudly against this perfect classical order. What exactly is Romanticism? Perhaps it’s a cultural rebellion of the individual tired of baroque propriety and classical constraints? Is it the rebirth of the Renaissance “I,” freed at last from the heavy rubble of formality, hoarsely proclaiming its right to exist? A tree tired of having its branches trimmed into elaborate shapes? Like the baroque figure, the romantic faces chaos alone—but while the baroque hero attempts to tame and structure chaos, the romantic lives in it fully. It’s well known that he “rebelliously seeks the storm,” and naturally, the storm finds him—usually hatless and wigless. The romantic doesn’t carve out a cozy corner in chaos; he amplifies it instead. With full sails he pursues his ideal, preferably eternal and unattainable. The entire passion and pain of Romanticism lie in pursuing something clearly impossible. If the romantic hero falls in love, it’s invariably with someone he cannot possibly have: a fairy, a Beautiful Lady, or even his own sister. The built-in tragedy is essential. While Baroque resigns itself to the drama of existence, Romanticism transforms suffering into art. The dissonance between what is, what you desire, and what you actually get creates tension that energizes the romantic hero. Romanticism thrives in eternal conflict with the world—but, weary of its predictability, turns its back on it and dives once more into chaos, as if that’s where it truly belongs. That’s why, when I play Liszt’s phenomenal sonata, I still can’t figure out: is this tragedy—or triumph? In the end, are Baroque, Classicism, and Romanticism really about art—or actually about us? And how exactly does today’s fashionable concept of Narcissism fit into all this? Isn’t contemporary narcissism simply our attempt to convince ourselves (and everyone else) that our personal chaos and emptiness conceal profound harmony? Perhaps, like baroque heroes, we strive to wrap our inner turmoil in perfectly filtered selfies and carefully curated stories. Or maybe, like romantics, we eagerly chase storms just to look more impressive posing against them? I don’t have answers (unless music counts). Perhaps there are no answers at all. Perhaps the true beauty lies hidden within the question itself.

FROM FUGUE TO FLAME (from Baroque to Romanticism)